No one-size-fits-all: better addressing intersectionality in climate-smart agriculture

Key messages

- South Asia is expected to be one of the three most concentrated regions of hunger in the world by 2050. Transforming both its agriculture and food systems is central to sustainable and equitable development and food security. Yet the critical roles of gender and intersectionality are not adequately incorporated for policy and program success.

- It is important to take both gender and intersectionality into account while analyzsing the context for more inclusive and effective policymaking, to make better use of resources and to better provide more tailored services.

- Livelihoods that are based on food systems are precarious for many of the most vulnerable and marginalised people, with climate change and variability posing a threat to food security.

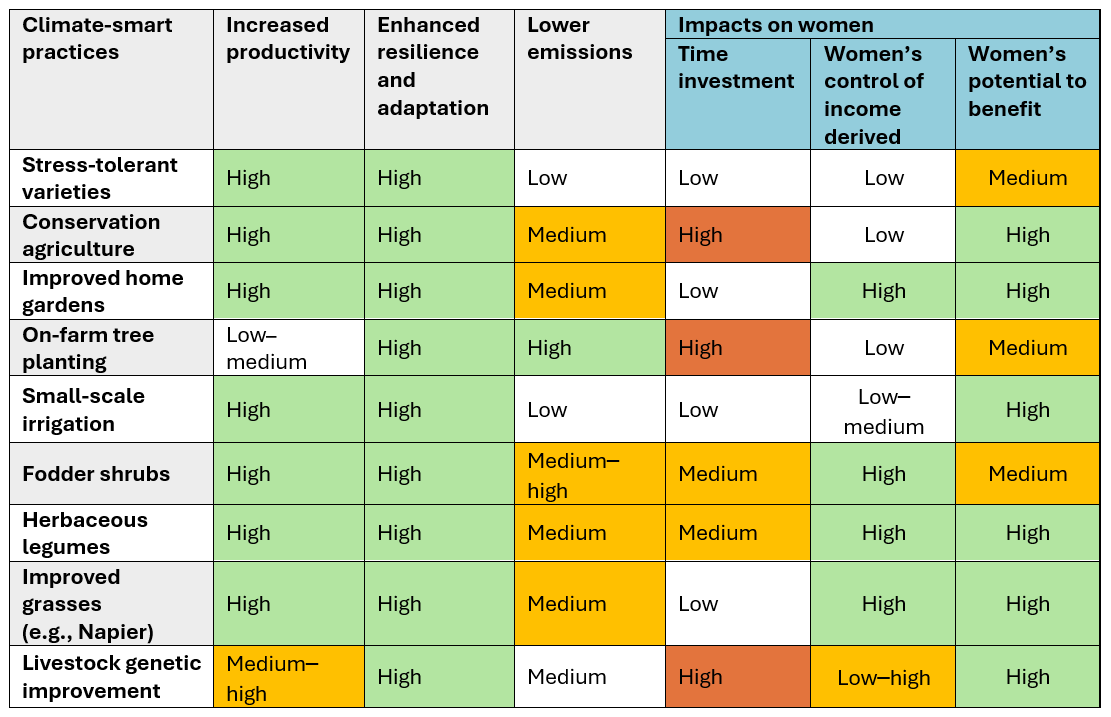

- Climate-smart agricultural practices vary in how they impact time burden, income and women’s ability to benefit from increased productivity. All impacts (positive and negative) should be assessed when planning and promoting climate-change adaptation practices.

- Gender-segregated data analysis, which also recognizes the most vulnerable, is essential to transform policymaking and project design to be inclusive.

Nuanced understanding of gender relations and intersectionality is necessary to design inclusive policies and programs

A number of intersectional factors like sex, age, class, race, and disability combine to create forms of privilege and disadvantage for an individual. Therefore, it is important to take both gender and intersectionality into account while analyzsing the context for designing and implementing policies, which allow better use of scarce resources for targeting the most vulnerable.

In our recent review covering South Asia, we examined studies that analyzed approaches, strategies and interventions that integrate gender and intersectionality dimensions of climate adaptation, resilience or mitigation in the agricultural sector. We adapted a framework to understand gender and social inclusion in climate-smart agriculture through the lenses of labor burdens, resource control, social norms and agency.

We found that despite growing evidence on the relationships between gender, agriculture and climate change, focus on intersectionality is limited when climate-smart agricultural interventions are developed and promoted.

Climate-smart agriculture can help mitigate negative impacts

As average global temperatures rise and climate shocks and stresses increase in frequency and intensity, climate-smart agriculture can help to ease the negative impacts on the sector.

New climate-smart agricultural technologies, techniques and activities can improve resilience and reduce climate impacts.

But gender and other intersectional factors like age, class, ethnicity and, disability underlie the many differences in how people engage with land and agriculture, including climate-smart interventions. Intersectional identities mediate people’s lived experience, their access to opportunities, their levels of social inclusion and their wellbeing.

Technological change needs to be gender-sensitive

How a technology impacts different socioeconomic groups in a population is highly context- specific. Women’s and men’s distinct roles and responsibilities in agriculture shape how they participate and lead in the agriculture sector.

The same technological improvement, say, for instance,, agricultural mechanization, might reduce the work burdens of a smallholder landowner, but remove a valuable income stream of paid labor from landless laborers. Poorer groups are less likely to own farm machinery, women are less likely to be perceived as able to operate farm machinery and, in both instances, technological improvements may have unforeseen negative consequences.

Technical improvements require additional support to enable vulnerable groups to benefit adequately from an intervention. For example, women in Bihar and Gujarat in India, when organized into dairy cooperatives, developed social and leadership skills. This also enhanced their ability to manage their cattle better by improving access to regular water supply and nutritious grasses and legumes, thereby improving their dairy yields and incomes.

On-farm adaptations to climate change must be gender-aware

We found that gender influenced adoption of on-farm improvements and opportunities for climate-smart agriculture.

Women’s access to and control over land remains a major limiting factor for adopting practices, alongside labor, access to water, and access to finance and credit. For example, an activity like planting trees might have different outcomes for women if planted in their home gardens (where they may have control over harvests) or on farmland (where frequently they have less control over the yields).

Specific climate-smart practices (see Table 1) varied in how they impacted time burden, income and women’s ability to benefit from increased productivity. All such impacts should be assessed when planning and promoting climate-change adaptation practices.

Table 1: Impacts on women of on-farm practices of climate-smart agriculture

Adapted from World Bank, FAO and IFAD (2015)

Climate-change mitigation efforts can be designed to reduce intersectional vulnerabilities

In a climate-smart village initiative of CGIAR in a district with predominantly Scheduled Tribes (social and economically marginalised) in Madhya Pradesh, in India, women comprise the majority of the agriculture workforce. These women are have multiply multiple vulnerable vulnerabilities due to the overlap of social and economic marginalisation experienced by Scheduled Tribes, and by gender, as women typically have lower agency and power in decision making and ownership. However, in this case, whilst while women did havehad lower reduced access to information, they enjoyed relatively more decision-making ability than women of some other non-Scheduled Tribes involved in the initiative.

Building on this initiative, village climate management committees encouraged 80 women’s self-help groups to undertake capacity building for climate-smart farming and related opportunities, such as selling surplus vegetables and selling biopesticides. The program trained women farmers to run custom hiring centres, renting out affordable farm machinery. This has increased the income of the women renting out equipment, and increased yields per hectare and efficiency of the farmland production, helping the women overcome the vulnerabilities of overlapping constraining intersectional characteristics.

New methods are being tried for collecting gender and intersectional data in South Asia

Most South Asian countries do not generate sex-disaggregated data in agriculture at macro- or meso-levels.

New approaches are being developed that gather more nuanced multi-dimensional intersectional data (e.g., caste, class, ethnicity, age, gender, marital and intra-household status, disability and land-holding size), investigating power relations and individual agency on barriers to participation, for example.

The information collection process needs to be carefully designed. With appropriate information, policy makers and program implementers will be able to explicitly consider individuals presenting with multiple vulnerabilities or risk enhancing characteristics in order to ensure that they are more likely to benefit. For example, an older woman with physical disability and limited literacy may require additional support to access and benefit from training in improved food processing and food safety for her food business. Training may need to be provided visually, in local language, and in a setting which that is physically accessible or with support workers who can ensure her transport. Given her potential for increased intra-household status as an elder, she may be able to access physical support in accessing the venue from family, but this should not be assumed.

Making climate-smart agriculture gender responsive

Our study summarised some key “dDos and dDon’ts” for making climate-smart agriculture more gender responsive:

- Invest in better understanding of people, their contexts and needs: Conceptual frameworks, research methodologies and impact analyses of climate change in agriculture need to integrate gender and intersectionality. Questions need to be framed to better understand power relations and intersectional complexities, such as “spirals of advantage or disadvantage”, how livelihood practices, gender and power influence outcomes in development and how self-perceptions feed into lived experience of power and ability to act and influence systems and structures.

- Create and tailor interventions that respond to varying contexts and target groups: We need to co-design iInterventions, technologies, analytics and programs need to be co-designed with and being led by, and engaging with, marginalised groups.

- Support ongoing dialogue, capacity and leadership building: Representation and voice are key elements of social and gender justice, and are critical elements in designing programs for climate change that respond to the challenges of social equity, food security and environmental sustainability.

- Policies on climate-smart agriculture needs to go beyond the farm gate: Wider structural issues, such as lack of access to credit and gendered norms around activity participation, alongside lack of capacity building, are significant barriers to improving livelihoods, increasing investment and capital availability on farms, market access, land use and tenure. But they also provide opportunities for taking remedial measures and therefore, need to be accounted for when designing effective climate-smart agricultural interventions.

- Policies should focus on gender-transformative outcomes: The emphasis for policies needs to shift to the outcomes of interventions, not just outputs or actions. This means explicitly designing interventions to increase the participation and decision-making power of vulnerable people.