Sources of bias when measuring women’s empowerment in fragile and conflict-affected settings: a story of four case studies

Photo credit: Axel Fassio/CIFOR

Accurately measuring women’s empowerment systematically across a variety of settings is critical to ensure equal access to market participation, control of the use of productive resources, opportunities for work and decision-making power. Collecting accurate data in fragile and conflict-affected settings, however, is a consistent challenge. For example, the timing of when survey data can be collected safely and differing household composition—due to migration tendencies motivated by safety or economic considerations—can complicate the use of standard survey techniques used to measure women’s empowerment.

In a CGIAR technical report, we present four case studies that highlight possible sources of bias when measuring women’s empowerment in fragile settings and generate insights about how to address these biases. The case studies aim to fill a critical gap in collective knowledge: while practical guides on measuring women’s empowerment exist, these resources do not address how to design survey tools measuring women’s empowerment within fragile and conflict-affected settings. Similarly, while practical guides exist for implementing impact evaluations in fragile settings with high levels of displacement, these resources do not discuss measuring women’s empowerment.

Case study 1: How changing the order of questions in a survey changes self-reporting about decision-making

The first case study presents results from a survey experiment implemented in Gombe State in northeast Nigeria that primed respondents to consider how displacement influenced their own decision-making power, before asking questions about their decision-making power within their household. The survey experiment randomized the order of two questions. Half of the respondents within displaced households were primed to reflect on how their decision-making power had changed since displacement before answering a question about who within their household normally makes decisions about given topics. The other half of the respondents received a questionnaire with these questions reversed. They were instructed to first answer a question about who within their household normally makes decisions about given topics and then were asked to reflect on how their decision-making power has changed since displacement.

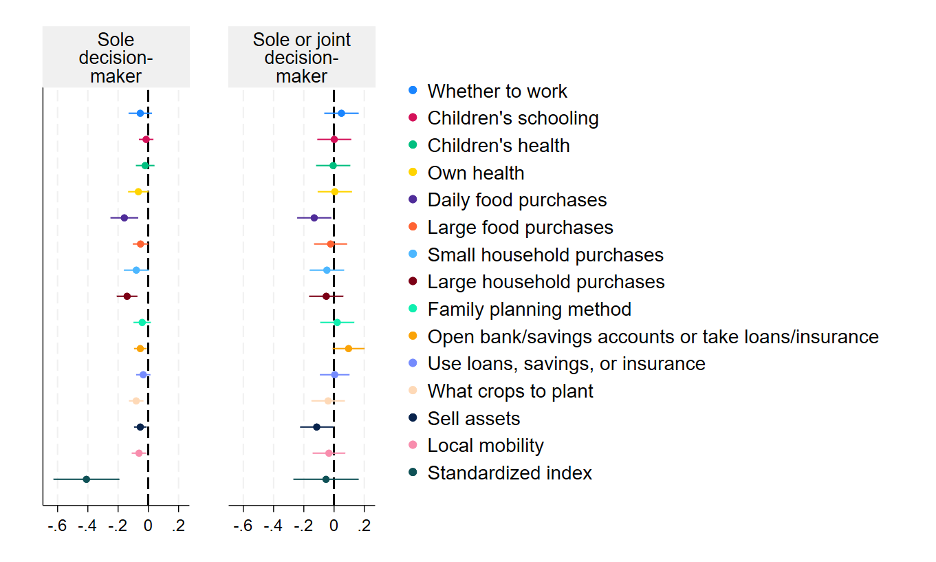

Figure 1 shows the effect of how a change in the ordering of questions influences how respondents report their own decision-making roles (i.e., either as the sole decision-maker or both sole and joint decision-making). Focusing on sole decision-making, we found that respondents who were asked to reflect on how their decision-making power changed since displacement first, were less likely to report that they themselves usually make decisions across all domains. The effect of this priming is statistically significant in the following six domains: (i) daily food purchases, (ii) large household purchases, (iii) opening bank/savings accounts or take loans/insurance, (iv) what crops to plant, (v) which assets to buy or sell, and (vi) local mobility. Additionally, when we constructed a standardized index that aggregates each of these domains, we found that framing leads to a 0.4 standard deviation reduction in the respondent’s reported decision-making power.

Figure 1: Priming and respondent decision-making power

Notes: Authors’ calculations of baseline data. Total sample size = 212. This figure reports the effect of question ordering on a binary variable indicating if the respondent normally makes decisions along each of the given domains, and a standardized index.

These results show that priming can affect measures of decision-making power. The statistically significant effects, reported in Figure 1, translate into percentage changes ranging from 52 percent (i.e., about daily food purchases) to 89 percent (i.e., about what crops to plant). Therefore, although our treatment is subtle—representing simply changing the order of two questions on our survey—we estimate priming effects with meaningful magnitudes.

Case study 2: How men’s migration influences measures of women’s economic empowerment

The second case study explored how men’s migration, and their physical absence from the household, influences measures of women’s economic empowerment in rural Tajikistan. In general, women living in migrant-sending households (where migrants are overwhelmingly male) were much more likely to be involved in making decisions on major expenditures. However, junior women in these households (i.e., younger women living within intergenerational households) were less likely to be involved in making decisions on both minor and major expenditures, crop income and mobility. These results demonstrate the importance of considering how household composition influences women’s decision-making power, and how factors that influence household composition (i.e., migration, respondent age, household wealth, etc.) are correlated with other variables of interest.

Case study 3: How exposure to conflict is correlated with how women respond to survey questions about household decision-making power and prevailing gender norms

The third case study used data from a survey implemented in southwest Nigeria to explore how exposure to conflict is correlated with how women respond to standard survey questions measuring household decision-making power and beliefs about prevailing gender norms. Women living in households that have been exposed to conflict in the previous 12 months report higher levels of household decision-making power, which led to significantly higher scores on an index measuring agency. Moreover, exposure to conflict led women to be significantly less likely to report believing in patriarchal social norms. This finding demonstrates the importance of understanding patterns of exposure to conflict when measuring women’s empowerment and agency in fragile settings.

Case study 4: How a phone survey was used to ensuring the safety of both enumerators and survey respondents

Finally, the fourth case study explored the use of a phone survey implemented in a post-conflict setting and reflected on an effort to shift from in-person data collection to a phone survey due to security concerns associated with ongoing conflict. This case study generated a discussion about important steps that the research team took to maintain the fidelity of survey questions, while also ensuring the safety of both enumerators and survey respondents. Future efforts should take unique care in (i) establishing trust of potential respondents and (ii) modifying survey questions for easier comprehension and response during phone surveys.

Within fragile and conflict-affected settings, a variety of factors might bias responses to questions about decision-making

These case studies highlight a variety of factors that might bias responses to questions about intra-household decision-making such as the structure of the questionnaire; the data collection approach; or the respondent’s exposure to conflict, internal displacement status, or household composition. This potential non-classical measurement error has important implications for empirical research and policy conclusions that consider measures of women’s empowerment and agency collected from households within fragile and conflict-affected settings. Overall, the insights from these four case studies demonstrate that existing survey tools designed to measure women’s economic empowerment or agency, especially those that include household decision-making components, need to be thoughtfully applied in such settings.

This work was supported by the CGIAR Science Program on Food Frontiers and Security. We are grateful to all funders who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund: https://www.cgiar.org/funders